Email: reecejordan98@hotmail.co.uk

Total Article : 168

About Me:18-year-old sixth form student, studying English Literature, History and Government and Politics. My articles will broadly cover topics from the current affairs of politics to reviews of books and albums, as well as adding my own creative pieces, whether it be short fiction or general opinion.

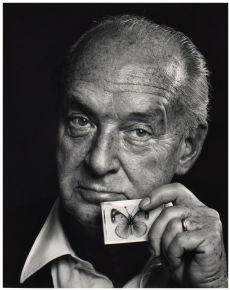

A theory has surrounded Nabokov’s prose, which is claimed to be one of the core reasons as to why his work is deemed so masterful and exhibiting of this enchanting quality. This view of his literature comes from the biographical detail that Vladimir Nabokov was a keen butterfly hunter, even to the extent that he published 18 science papers in the field of lepidoptery, and from 1942 to 1948 was de facto curator of lepidoptery at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. As such, critics have come to view Nabokov’s prose as works of art that exhale the breath of metamorphosis. Indeed it is clear to see why some have come to that conclusion – much of Nabokov’s work involves a type of change. But I would like to put forward the argument that his prose is more concerned with mutation than metamorphosis. It is a similar premise, but with, I believe, a crucial difference. Metamorphosis follows a pattern of nature, something we look at with a glint of anticipation in our eye. Mutation, however, is nature’s swift underhand deception – something we don’t expect. This is a far more apt way to look at Nabokov’s work. In Lolita, for example, Nabokov mutates the nature of Lolita’s ‘love’ into one of ritualised activity for money, adding a clog into Humbert’s idealised fairytale narrative of the story. If we look at Laughter in the Dark, we see a similar mutation of the dynamic between love-struck Albinus and his deceptively cruel mistress, Margot. With the masterful inclusion of Rex – a figure of unrequited reverence for Albinus and absolute desire for Margot – Nabokov distorts and mutates the dynamic of the relationship into one of playful cruelty. Mutation also has a commonality with another hobby of Nabokov’s – chess. This is something that Nabokov himself has claimed to lace his novels with. In the foreword to The Luzhin Defense, Nabokov asks his reader to be attentive to the way in which the structure of the novel replicates the masterstrokes of a great chess player, which catch us as the reader off-guard. These arbitrary strokes, these sudden mutations, are key to Nabokov’s novels.

Later in the lectures, Nabokov drifts less from his own view of what great literature is (though this is subtly carried forward), and inclines more on to what makes a great reader.

He states:

“In reading, one should notice and fondle details. There is nothing wrong about the moonshine of generalization when it comes after the sunny trifles of the book have been lovingly collected. If one begins with a readymade generalization, one begins at the wrong end and travels away from the book before one has started to understand it. Nothing is more boring or more unfair to the author than starting to read, say, Madame Bovary, with the preconceived notion that it is a denunciation of the bourgeoisie. We should always remember that the work of art is invariably the creation of a new world, so that the first thing we should do is to study that new world as closely as possible, approaching it as something brand new, having no obvious connection with the worlds we already know. When this new world has been closely studied, then and only then let us examine its links with other worlds, other branches of knowledge.”

Image Credits: wikipedia.co.uk

0 Comment:

Be the first one to comment on this article.