Email: reecejordan98@hotmail.co.uk

Total Article : 168

About Me:18-year-old sixth form student, studying English Literature, History and Government and Politics. My articles will broadly cover topics from the current affairs of politics to reviews of books and albums, as well as adding my own creative pieces, whether it be short fiction or general opinion.

Are you capable of an evil action? If your immediate response to that question is one of defiance, that you believe you understand yourself, your integrity, and your incapacity for immorality and evil, then you are not alone. But suppose the question negated the notion of capability and was instead framed: what causes you to do an evil action?

This is the question professor of psychology, Dr. Philip Zimbardo of Stanford University, intends to explore on his book The Lucifer Effect. Instead of searching for dispositional discrepancies in humanity (i.e. ‘evil actions are caused by evil people’), Zimbardo begs us to be more attentive to the situational and systemic factors surrounding such actions of evil.

The book revolves around an experiment conducted in the 1970s, the notorious Stanford Prison Experiment, or SPE for short. This experiment consisted of Zimbardo and his team creating a false prison wherein there would be ‘prisoner’ and ‘guard’ occupants. Both the prisoners and guards were specifically selected as ‘good apples’ and ordinary people by means of psychological testing, and were randomly designated their respective duties. Zimbardo provides an account of the experiment in present tense through the lens of himself playing both psychologist and superintendent. The experiment begins somewhat benignly after the ‘prisoners’ are arrested: laughs are the usual response to orders given by the guards; their situation is comically under the veil of the knowledge of it being an experiment.

But soon, indeed, very soon, things begin to change. Position yourself, if you will, in the role of a ‘prisoner’. As the day progresses you are banned from addressing yourself and others by name, and are instead given a specific number. You have been stripped naked in front of everyone, the guards have joked about the size of your and your fellow inmates’ genitalia, you have been forced to memorise 17 rules by heart, and they have now you got you lined up for ‘counts’. For failing to memorise your number you are forced to do 30 press-ups and then 20 more for fun. You can now imagine, hopefully, that what you signed up for some income over the summer, is now very real. So real that it takes one of the prisoners just one day to show mental unease, and is sent home.

As the experiment carries on, we begin to see that the corrosion of the guard’s moral integrity with their newfound power. They began to keep prisoners in the ‘Hole’ – solitary confinement – for longer than an hour (the maximum time allowed), forced prisoners to do push-ups with other prisoners sitting on their backs, and even got them to imitate sodomy with other inmates, purely for their humorous pleasure. Some guards abstained from enforcing such ridiculous tasks on the prisoners, and earned their epithet as ‘good guards’. However, Zimbardo refrains from such generosity in his analysis and instead accuses them of the ‘evil of inaction’. That is, in other words, a rebuke of the way in which they allowed the other guards to exercise their power.

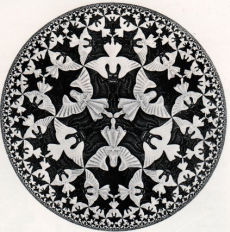

Image Credits: sites.psu.edu

0 Comment:

Be the first one to comment on this article.