Rushdie takes Al-Queda out of its political-religious framework for a moment and reconstructs it as an art movement; an analogy which seems even more apt when employing it in regard to Al-Qaeda’s demented offspring, ISIS; whose extensive use of hellish stunts - from the mass shootings of Shia Muslims, to the beheading of Libyan Christians, to the burning of a Jordanian pilot, to the machine gunning of theatre-goers in Paris just the other week – have enabled them to make us reimagine our world as one in which one can never be safe, no matter how many frontiers appear to separate you from them.

In light of this analysis, Rushdie poses a question he appears to leave unanswered, which is “On the other side of that frontier, we find ourselves facing moral problem: how should a civilised society – in which […] there are limits, things we will not do […] because we consider them beyond the pale […] respond to an attack by people for whom there are literally no limits at all […]?” (437)

Frontiers of Art and Expression

With this newfound scepticism for the frontiers of imagination in light of 9/11, which brought about the haunting realisation that it can be employed paradoxically for the means of destruction and well as creation, Rushdie turns to artists themselves. He notes how, increasingly, artists today are coming under criticism for setting out, like terrorists, to shock rather than to create something new, saying, “Once the new was shocking not because it set out to shock but because it set out to be new. Now […] the shock is the new”. (440) And continuing this linkage between what Rushdie calls the “frontierlessness” of artists and terrorists, Rushdie goes on to observe that because of the desensitising nature of shock artists are having to go to increasing lengths so as to continue to maintain people’s attention, saying, “the artist who seeks to shock must try harder and harder […] this escalation may now have become the worst kind of artistic self-indulgence.” (440) The radical and once meaningful act of crossing frontiers has, to Rushdie, been reduced by the art profession to an exercise in vanity.

This quite disconcerting trend in contemporary art prompts Rushdie to ask: “in the aftermath of horror, of the iconoclastically transgressive image-making of the terrorists, do artists and writers still have the right to insist on the supreme unfettered freedoms of art?” (440) This is a question which has emphatically come to the fore over the past ten years and Rushdie responds to this question by looking at Anthony Julius’ book Transgressions: The Offences of Art, which surveys how art has transgressed moral and political frontiers.

He makes particular reference to Julius’s examination of the nineteenth century Impressionist Edouard Manet, noting how “in Olympia, a picture of a whore […] he visited the frontier between art and ‘pornography’ […] crossing the boundaries between the nude (an aesthetic, unerotic idea) and the naked woman, gazing out of the picture with frankly erotic intent.” (440-1)

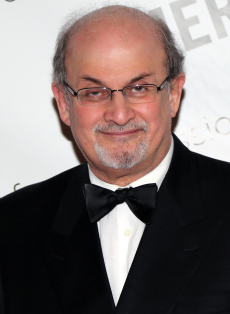

Image: By PEN American Center [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

0 Comment:

Be the first one to comment on this article.