This year marks the 100 year Anniversary of the beginning of the First World War in which lots of brave men fought and died facing new weaponry, commanded by 'old fashioned Generals'. Many people consider people such as Sir General Douglas Haig to have been a fool and sent millions of men to their deaths foolishly, but could anyone have used any better tactics given the level of knowledge of warafre in the First World War? Here's one argument to get debate started:

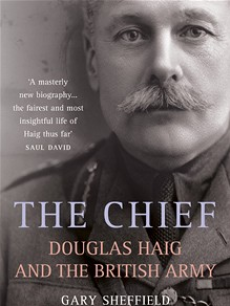

For many, Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig is considered the worst British military leader of World War One, infamously entitled ‘The Somme Butcher’ for his role in ordering hundreds of thousands of the BEF (British Expeditionary Force) to their deaths in a disastrous series of events at the Battle of the Somme. In Churchill's devastating judgment, Haig "wore down alike the manhood and the guns of the British army almost to destruction." Keegan also reflects mercilessly "On the Somme, [Haig] had sent the flower of British youth to death or mutilation; at Passchendaele he had tipped the survivors in the slough of despond." Despite the atrocities Haig is excused by some as unluckily leading the British in a war that outdated our military. However we view his character, there is no doubt that multiple changes were made as a result of Haig’s leadership in The First World War; many that proved to be highly important in the short term.

On one level the short term importance of Haig’s leadership is prevalent in the number of men killed under his command. Beginning with the infamous battle of The Somme, Haig is heavily criticised for his heavy reliance on outdated ideas of warfare, from his personal war diary - “We’ll do better by getting as large a force of attackers as possible, and fighting the enemy in the open.” An example of these tactics is his desire to use cavalry as a decisive spearhead into the enemy lines, a method that was suicide in the face of modern innovations such as the machine gun and tactical use of barbed wire. An article from the Manchester evening news in 1998 by A.Grimes (a journalist) labels Haig “an idiot” and entitles him “The Somme Butcher”. For his incompetence and stubbornness Haig sacrificed many young British men, but it was said to be not in vain as the British government vowed to have “no more Sommes”. What this effectively meant was that Haig’s leadership at the Somme proved highly important in the short term as the Government were determined to learn from those mistakes suffered by Haig in a war of attrition where they couldn’t afford to lose so many men in such a short space of time. One such improvement to be taken from this was the ineffectiveness of long drawn out bombardments thus the ‘creeping barrage’ was adopted. ‘The Good Soldier,’ a biography of Haig written by G.Mead, supports the concept that Haig was simply ‘unlucky’, in command at the wrong time; he struggled to manage “a massive army, weak allies, pushy politicians, a determined enemy and unreliable new technology, like tanks.” Though this source condemns Haig for stubbornly sticking by “old tactics”, it also illustrates the short term importance of poor organisation and logistics in the British army in World War One which Haig struggled with; a matter that was immediately addressed following the devastating Battles of The Somme and Passchendaele. After the Somme, in the interest of improving logistics and communications signallers were told to follow close behind the forward attack laying their lines in a ladder formation so that if one part of the line was broken, messages could still get through. This was a major development. Greater use was also made of intelligence. Aerial reconnaissance photographs proved very useful as did the intelligence reports from the airborne spotters. Furthermore, lessons were learnt from Haig’s mistakes at Passchendaele, a battle that infamously hosts the largest number of soldiers to ever drown in a land battle. Firstly that weather is the most important and fundamental factor in a battle fought across open land such as the majority in wars of attrition like the First World War and leading on from this that weapons may work properly in good weather, but it is unlikely that they will be effective when the weather is poor.

Haig was granted the rank of Field Marshall by the king following the year of 1916 thus the monarchy and powers at be in Britain clearly considered Haig’s darkest hours of his long and decorated military career victories. There is no doubt that the opposition were crippled at the Somme with German death tolls estimated at 500,000, almost 100,000 more than the British losses; in a war of attrition this can only be considered a victory. In addition to this the battle bled dry German reinforcements to Verdun where the French were making a gallant stand; this was actually the primary objective of the battle. Though questionable in hindsight, Haig’s tactics for the Somme seemed logical and form the basis of the idea of a continuous advancement that changed the way war was fought a few years later. In his war diary Haig criticised Rawlinson’s proposals as “weak” and stated that it was more practical to fight “the enemy in the open” which, when we consider the way the elite German storm troopers were used so effectively in 1918, paves a foundation for the path away from a sluggish war of attrition thus I would argue that Haig’s willingness to divert from ‘commonly accepted’ tactics is of great short term significance in the style with which the war was fought the next few years.

(So Haig was clearly a controversial character and probably made several correct decisions as well as many poor decisions, but what's your opinion? History is all about interpretation, so why not write some articles of your own with your responses and opinions? Or comment on this article if you prefer. I look forward to reading them!

0 Comment:

Be the first one to comment on this article.