Email: EllaTournes@bexleygs.co.uk

Total Article : 45

About Me:Sixth form student currently studying English Literature, Drama and Theatre Studies, Classical Civilisation and History.

It could be argued that the only woman Orwell deigns to elevate is Winston’s mother because she a woman that doesn’t actually exist within the world of the novel he’s writing - she isn't, in this context, a 'real' woman. However, I don’t believe that Orwell is elevating Winston’s mother – he is elevating the past she symbolises. This can be seen through the phrase, ‘His mother’s death, nearly thirty years ago, had been tragic and sorrowful in a way that was no longer possible’. The syntax throws emphasis on the second half of the main clause, by breaking up the main clause with subjunctive information, allowing the reader to acknowledge the mothers death, but for the main focus of the sentence to be on the juxtaposition between the power and emotion of the ‘tragic’ and ‘sorrowful’ and the notion of that being ‘no longer possible’. The elevation of that power and emotion, and the loss of that, is therefore presented by Orwell as being more harrowing than the mother’s death – the loss of the past is more harrowing to Winston than the loss of his mother. As a female character, this undermines her.

There is no elevation at all, however, in Huxley’s presentation of Linda. Linda is shown no mercy throughout the novel, by either the characters or the narrative itself. Upon introduction, Huxley projects Lenina’s disgust at Linda’s appearance through free indirect discourse. She is described in a very visceral manner – Huxley refers to ‘the sagging cheeks with purplish blotches’, ‘the red veins on her nose and bloodshot eyes’ and ‘the bulge of the stomach, the hips’. He also refers to her as ‘the creature’. The repeated use of ‘the’ rather than ‘her’ dehumanises Linda, and the use of the word ‘creature’ makes her seem animal. This, combined with the semantic field of body parts, and the plosive consonance created in the words, ‘purplish’ ‘bloodshot’ ‘bulge’ ‘stomach’ and ‘hips’ make Linda seem harsh and grotesque to the reader. Although Huxley is obviously projecting this description from Lenina’s perspective, it’s very difficult for a reader to experience pathos for Linda at any point in the novel, when she is reduced to an animal upon initial description. Huxley also undermines Linda by giving her an obsession with the materialistic. Throughout her first speech to Lenina, Linda nostalgically laments over ‘civilised clothes’, ‘a piece of real acetate silk’ and ‘viscose velveteen shorts’ – here, Huxley creates a semantic field of the synthetic, making Linda seem false and transparent. He also creates irony with the materials he has Linda describe – the phrase ‘real acetate silk’ is oxymoronic; a piece of silk cannot be both real and acetate. This presents Linda as stupid. The way Huxley presents Linda as an older ‘fat’ woman, with a consciously crafted obsession with the synthetic can be contrasted with the presentation of the singing prole woman that Winston sees in ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’. Orwell uses the natural world to emphasise the woman’s beauty. He compares an older woman and a younger woman as being ‘as a rosehip is to a rose’. He then asks ‘why should the fruit be held inferior to the flower?’. The use of the words ‘rosehip’ and ‘fruit’ both project positive imagery, of nature and beauty. They also suggest a practicality that can be compared to the usefulness of the mothering role – ‘fruit’ is used for feeding, and ‘rosehip’ is used for medicating, both nurturing roles that fall into the realm of motherhood. Orwell compares the motherhood to the beauty of the natural world, therefore elevating it. He also describes her ‘characteristic attitude’, her ‘thick arms reaching’ and her ‘powerful mare-like buttocks’ her ‘body, like a block of granite’ – phrases that all bear connotations of strength and brawn. Orwell then calls the woman ‘beautiful’. The idea that a woman who is powerful and strong (traits often attributed to males) can still be beautiful is inherently feminist, and is arguably ahead of Orwell’s time. Huxley’s presentation of an old, fat, ugly woman, however, comes across as tired and clichéd.

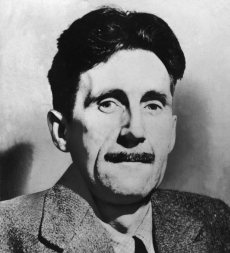

Source: https://www.google.co.uk/search?q=1984&espv=2&biw=1093&bih=490&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjgjYaylMnQAhWBBcAKHYNXA4cQ_AUIBigB#tbm=isch&q=george+orwell&imgrc=pZpoaJqIRFoSIM%3A

0 Comment:

Be the first one to comment on this article.