Email: ZYVC057@live.rhul.ac.uk

Total Article : 213

About Me:I'm a graduate student studying International Criminal Law and first started writing for King's News almost 4 years ago! My hobbies include reading, travelling and charity work. I cover many categories but my favourite articles to write are about mysteries of the ancient world, interesting places to visit, the Italian language and animals!

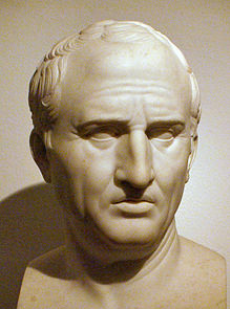

Marcus Tullius Cicero was a Roman philosopher, laywer, writer and stoic. The Romans adopted many traits of Ancient Greek philosophy, only to then differenciate themselves from it. Romans tended to be men of action, warriors and workers, whereas Greeks are thinkers, they love to consider life-long questions and ponder on the meaning of everything. Cicero was a statesman born in 106BC who read philosophy. He was the inversion of Aristotle: the good life for Aristotle was a life of complemplation and to gain this one must be involved in the polis whereas Cicero was a man of action who merely engages in philosophical affairs at times. He was an equestrian, middle class, who became a counsel, he achieved a political office in a higher class, he achieved class mobility. He was also a great prose writer for the Ancient World; he wrote about a Rome that was deep in decline.

Alongside Cicero's more political works, the author is famous for his 'Laelius de Amicitia', a treatise on friendship written in 44BC. Cicero ponders on his own friendships whilst thinking about the true meaning of the word, using the relationship between Scipio Aemilianus and Laelius to express his own inner thoughts on the topic. Laelius dominates the majority of the work as he reflects on the death of his friend Scipio.Throughout the entire book, Cicero emphasises the virtue of friendship and its deep meaning to all of mankind.

Below you can find a few initial passages of the treatise in Latin with the English translation also.

Laelius De Amicitia

I. 1. Q. Mucius augur multa narrare de C. Laelio socero suo memoriter et iucunde solebat nec dubitare illum in omni sermone appellare sapientem; ego autem a patre ita eram deductus ad Scaevolam sumpta virili toga, ut, quoad possem et liceret, a senis latere numquam discederem; itaque nulta ab eo prudenter disputata, multa etiam breviter et commode dicta memoriae mandabam fierique studebam eius prudentia doctior. Quo mortuo me ad pontificem Scaevolam contuli, quem unum nostrae civitatis et ingenio et iustitia praestantissimum audeo dicere. Sed de hoc alias; nunc redeo ad augurem.

2. Cum saepe multa, tum memini domi in hemicyclio sedentem, ut solebat, cum et ego essem una et pauci admodum familiares, in eum sermonem illum incidere, qui tim forte multis erat in ore. Meministi enim profecto, Attice, et eo magis, quod P. Sulpicio utebare multum, cum is tribunus pl.[plebis] capitali odio a Q. Pompeio, qui tum erat consul, dissideret, quocum coniunctissime et amantissime vixerat, quanta esset hominum vel admiratio vel querela. 3. Itaque tum Scaevola cum in eam ipsam mentionem incidisset, exposuit nobis sermonem Laeli de amicitia habitum ab illo secum et cum altero genero, C. Fannio M. f. [Marci filio], paucis diebus post mortem Africani. Eius disputationis sententias memoriae mandavi, quas hoc libro exposui arbitratu meo; quasi enim ipsos induxi loquentes, ne "inquam" et "inquit" saepius interponeretur, atque ut tamquam a praesentibus coram haberi sermo videretur.

4. Cum enim saepe mecum ageres, ut de amicitia scriberem aliquid, digna mihi res cum omnium cognitione, tum nostra familiaritate visa est. Itaque feci non invitus, ut prodessem multis rogatu tuo. Sed ut in Catone Maiore, qui est scriptus ad te de senectute, Catonem induxi senem disputantem, quia nulla videbatur aptior persona, quae de illa aetate loqueretur, quam eius, qui et diutissime senex fuisset et in ipsa senecture praeter ceteros floruisset, sic, cum accepissemus a patribus maxime memorabilem C. Laeli et P. Scipionis familiaritatem fuisse, idonea mihi Laeli persona visa est, quae de amicitia ea ipsa dissereret, quae disputata ab eo meminisset Scaevola. Genus autem hoc sermonum positum in hominum veterum auctoritate, et eorum inlustrium, plus nescio quo pacto videtur habere gravitatis; itaque ipse mea legens sic adficior interdum, ut Catonem, non me loqui existimem. 5. Sed ut tum ad senem senex de senectute, sic hoc libro ad amicum amicissimus scripsi de amicitia. Tum est Cato locutus, quo erat nemo fere senior temporibus illis, nemo prudentior; nunc Laelius et sapiens (sic enim est habitus) et amicitiae gloria excellens de amicitia loquetur. Tu velim a me animum parumper avertas, Laelium loqui ipsum putes. C. Fannius et Q. Mucius ad socerum veniunt post mortem Africani; ab his sermo oritur, respondet Laelius, cuius tota disputatio est de amicitia, quam legens te ipse cognosces.

Laelius on Friendship

I. 1. Quintus Mucius Scaevola, the Augur, used to relate many a tale about Gaius Laelius, his father-in-law, with perfect memory and in a pleasant style, nor did he hesitate whenever he spoke to call him Wise. Now I, on assuming the dress of manhood, had been introduced to Scaevola by my father with the idea that, so far as I could and it was permitted me, I should never quit the old man's side. And so I used to commit to memory many able arguments, and many terse and pointed sayings of his, and I was all on fire to become, by his skill, more learned in the law. And when he died, I betook myself to Scaevola the Pontifex, who I venture to say was beyond doubt the man in our state most distinguished for ability and justice. But I will speak of him another time; I now resume my remarks about the Augur.

2. I remember much that he said on many occasions, but especially that once, when he was at home sitting according to his wont upon a fauteuil, myself and a very few intimate friends being with him, he fell into a discourse on a subject which happened at that time to be on many people's lips. For of a surety, Atticus, you remember, and remember all the more vividly because you were a close friend of Publius Sulpicius, how deep was men's surprise and disgust when he, as tribune of the people, was estranged by a deadly feud from the then consul, Quintus Pompeius, a man with whom he had lived in the strongest bonds of affection.

3. And so at that time, since Scaevola had chanced to mention that very occurrence, he set forth to us that discourse concerning friendship which Laelius had held with him and his other son-in-law, Gaius Fannius, the son of Marcus Fannius, a few days after the death of the younger Africanus. I committed to memory the chief opinions maintained in that conversation, and I have set them forth in this book in my own way; for I have brought upon the boards the very men themselves, so to speak, in order that the words 'say I', and 'says he' might not be scattered too thickly, and that the discussion might seem to be held as it were by men present face to face.

4. For since you often pleaded with me to write something about Friendship, the subject seemed to me worthy alike of the consideration of all and our own friendship in particular. Therefore I have taken pains--no unwilling task--to benefit many at your request. But, just as in the "Cato Major," which I dedicated to you, on the subject of Old Age, I introduced Cato discussing it in his old age, because no personage appeared to me more fit to speak of that time of life than he, who had not only been an old man for a very long time, but had also even in his old age outstripped other men in prosperity; so, since we had learned from our fathers that the friendship of Gaius Laelius and Publius Scipio was especially proverbial, the personage of Laelius seemed to me a proper one to set forth those very points about friendship which Scaevola had called to mind as having been discussed by him. Now this kind of discourse seems in some strange way to have more weight, if it rests on the authority of men of old, particularly such as are famous; and so, when I myself am reading my own writings, a feeling at times comes over me, that I imagine Cato, and not myself, to be speaking.

5. And just as in the De Senectute I as an old man wrote to an old man on the subject of old age, so in this volume I, the sincerest of friends, have written to a friend about friendship. In my former book the spokesman was Cato, than whom there was hardly anybody of greater age in those days and none wiser; while in this treatise Laelius, who was both wise (for so he was esteemed) and distinguished for the celebrity of his friendship, shall speak about friendship. I should like you for a little while to turn your attention from me, and fancy Laelius himself to be speaking. Gaius Fannius and Quintus Mucius come to their father-in-law after the death of Africanus; the conversation is opened by them and Laelius replies. To him belongs the whole of this discourse about friendship, and while reading it you will recognize your own portrait.

Image: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9a/M-T-Cicero.jpg/220px-M-T-Cicero.jpg

0 Comment:

Be the first one to comment on this article.